Pakadi's fauji

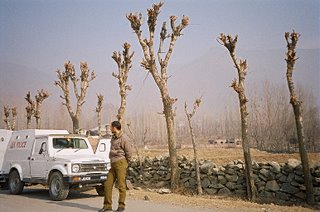

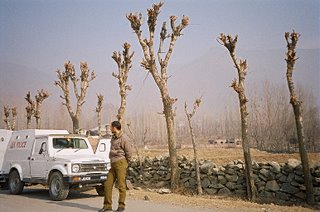

After three days of snow the roads are for the first time clear for movement. Thankfully the road connecting Haripora and Srinagar is NH1A, the lifeline of army supply. Had it been some other road we would still be stuck, like the tourists in Gulmarg who have now started selling their cameras and jackets to pay hotel bills for overstaying. NH1A is strategically very significant. In the Kargil war it was Pak army’s main target. Cutting it off meant easy capture of the Leh area. Today the road looks very different. Fields on both sides are covered with over a feet of snow and the vast whiteness on the sides is contrasted only by leafless trees or the solitary security man at every kilometre. Standing alone for 12 hours with feet dug deep in snow may be his duty but not quite something he enjoys. Who knows where he belongs. He has no stake here. Before he came here probably he didn’t even know K of Kashmir. Like a robot he just followed orders and marched north. Because if he didn’t, his wife and children, probably in some far off village in UP or Bihar would starve to death. With about a fortnight of training on an automatic he holds it like a baton, as if completely oblivious of its lethal power. The machine dangles from his shoulders like a liability. When he moves, he drags it like a broom. When he is bored, tired he uses it, the only companion he has in this wilderness, as a prop to rest his tired legs. His bodyweight on the gun that’s supposed to bring peace. It does. It fires. The bullet rips apart the chin making its exit through the temporal lobe. Pakadi’s fauji is no more. He has died a ‘martyr’s’ death.

Snow, snow, snow

Once it started snowing, for three days we didn't have much to do. So I am clubbing the three days here...On the first morning of 2006 I was woken up by a loud shout. Quyum saab had  entered our room shouting, “Fools get up, it’s snowing!” We jumped out of the bed and straight on to the window. Boy, frankly speaking, I had never witnessed something like that in my entire life. White earth, white trees, white mountains, white river, white huts (yes all of this was visible from our window), white everything; the whole Valley was as if covered with pristine white satin. Vast tracts of snow till the horizon (in fact there was no horizon as a white earth would meet a white sky). Just too much of white. I wonder why the washing powder ad guys haven’t got an idea yet. The whole of Kashmir looked like a greeting card, as if divinity had descended on earth to wish Happy New Year. I must be blessed to have been there.

entered our room shouting, “Fools get up, it’s snowing!” We jumped out of the bed and straight on to the window. Boy, frankly speaking, I had never witnessed something like that in my entire life. White earth, white trees, white mountains, white river, white huts (yes all of this was visible from our window), white everything; the whole Valley was as if covered with pristine white satin. Vast tracts of snow till the horizon (in fact there was no horizon as a white earth would meet a white sky). Just too much of white. I wonder why the washing powder ad guys haven’t got an idea yet. The whole of Kashmir looked like a greeting card, as if divinity had descended on earth to wish Happy New Year. I must be blessed to have been there.

The next few hours we went mad clicking pictures propping ourselves up on every stupid thing we found — the idea was to have as many snaps as possible before the snow stopped. We were in a hurry for no reason, we found out. It kept snowing relentlessly through the day. We were all locked up inside, munching on kebabs and sipping on alcohol.

This was the time every Kashmiri loved — for farmers it meant good crops in summers and for others it meant a long sabbatical, for snow in January wouldn’t melt till Feb. But for one Kashmiri, it was special. Shafi saab (Quyum saab’s cousin) could now sit for days and play cards. He has a local record to his name: played cards continuously for three days. Certainly, it was shared by some equally enthusiastic friends. An example of this we saw in the afternoon. Shafi saab has constructed a new residence a few yards away from his ancestral home. The greatest feature of the new residence is its living room equipped with a hammam. (For those who don’t know, hammam is a kind of fireplace beneath the floor. In winters Kashmiris use it to keep their room warm.) Shafi saab’s children are fighting the snow to ignite the hammam. For them it’s a picnic of sorts. But in their enthusiasm they have put a little too much of wood and the floor has turned into a hot tin roof. The sitting postures in the room shift gradually, from bums-on-the-floor to squatting, to standing, to jumping… But the game continues. Talk about sporting passion.

It’s all great fun, but by evening it has got to too much of a good thing. The whole Kashmir has come to a standstill. Srinagar is shut. All roads blocked, no flight take offs. I know I am stuck. I had plans of returning by road. But that’s out of question. I am informed that in this kind of weather, even after the snow is cleared, there are chances I could be stuck up on my way to Jammu for upto 20 days. Everyone is now having fun at the expense of my distress. “Beta tum to fans gaye… ek kaam karo, Feb tak ruko aur is bar garmiya dekh kar hi jana…” Yeah, rrrright…

With a sinking heart I go to the bed only to wake up to more snow next morning. This time it’s even heavier. All the guests who had come visiting on the New Year’s eve are stuck at our place. Lot of discussions, lot of gossip and loads of stories. One among the guests, known as Tehsildar saab (he is the tehsildar for Kangan Tehsil), is narrating his travails in his a-year-and-half (1990-91) posting in Talel, a high altitude region in Kashmir, also a high infiltration zone. ‘Working in Talel-Gurej areas is not easy, but if government sends you there you have no option. More than 10 feet of snow and wind whistling past you through night and day, it can’t get tougher. In winters it gets terribly worse. There are blizzards that stop all activity, there is very little anyways. All you do is sit inside and eat meat. Yes that is the only thing available to eat. It’s freezing (for want of a better word) cold at –30 degrees. No one stays on the ground floor; it’s covered in snow. And if someone dies, he remains buried for the next six months in snow. Only when the summers arrive anyone can hope to dig earth. There is no power, there is nothing. You just have to sit and wait for the winters to get over. But here, in the middle of it we have got marching orders (transferred). In so much of snow no vehicle can ferry us. And to avail of a vehicle we must reach Bandipore, 86 km from Talel. Some ten of us start our march on foot in more than 10 feet of snow. In such weather even the snow has frozen and walking on it is like walking on glass. We must be careful as we are going downhill. Everyday we are supposed to cover 20 km in order to reach the next BFS camp for the night stay. There is no scope of getting tired and relaxing in the middle. It could anytime start snowing and with no shelter one could be buried. It was an ultimate test of endurance. Amongst us there was also this elderly fellow who could not bear this ordeal and requested us, ‘You guys go ahead and leave me here. Let me die peacefully if I have to.’ But we somehow persuaded and gave him the courage to walk again. We walked for five continuous days before we reached Bandipore.”

There were many more stories but either not too interesting or too regular to deserve a mention here (I am cutting short on terrorism stories as advised by some discerning readers). It again snowed through the day. And now the panic that was once married to me was engaging one more — my colleague. “Yaar aise hi baraf girti rahi to lagta hai mai bhi nahi ja paunga… Kal dekhna boukhala ke suraj nikalega…” Talk about height of optimism. But he was right; the next morning sun was glaring on us. The Valley looked even more beautiful now. With fog disappearing, visibility increased; the snow-clad peaks with a diamond glint seemed to dazzle and overpower the mortals at its foot. Tree shadows cast on snow made for beautiful photo frames. We once again headed out with our cameras.

The afternoon was fixed with Shafi saab. We went to, once again, for the last time, enjoy his hammam. This time it was much controlled and nice. The lesson from the earlier experience was well taken. Bhabhi served us cake (in Kashmir they are always serving cake) and asked, “Kaun si chai piyenge? Kashmiri ya Lipton?” Another question that everybody asks. Wonder how Lipton has invaded the Valley. Anyways, another discussion on Kashmir ensues (I shall spare you the details) till it’s evening and time to go before it’s too dark. We must leave early and Shafi saab accompanies us. We ask him to stay with us for a while but he pleads: “Sher ka khatra hai.” In the nights, leopards from the jungle stray into villages to hunt cattle and dogs.

The afternoon was fixed with Shafi saab. We went to, once again, for the last time, enjoy his hammam. This time it was much controlled and nice. The lesson from the earlier experience was well taken. Bhabhi served us cake (in Kashmir they are always serving cake) and asked, “Kaun si chai piyenge? Kashmiri ya Lipton?” Another question that everybody asks. Wonder how Lipton has invaded the Valley. Anyways, another discussion on Kashmir ensues (I shall spare you the details) till it’s evening and time to go before it’s too dark. We must leave early and Shafi saab accompanies us. We ask him to stay with us for a while but he pleads: “Sher ka khatra hai.” In the nights, leopards from the jungle stray into villages to hunt cattle and dogs.

That reminds me of another interesting story that was narrated to us the other day. One of Quyum saab’s neighbours was once guarding his apple orchard in the night sitting atop a machaan (a platform high above the ground, with bamboo sticks pillaring the structure). Bears had been a menace for a while and being a hunter he thought he would kill one that day. With his gun all loaded, he waited till midnight for the beast. It finally arrived. There was some commotion in the bushes near his door and with the precision of an Olympic shooter he pierced the bullet right through its heart. Dead on the spot. With a pride-in-skill suffused smile when he went to check out the carcass, it turned out to be a dead body. The dead body of his father, who had come out to pee.

Rind posh mal...

December 31, 2005Once again we are late. It’s already 9am. It’s terribly cold as well and so I sit in the kitchen with a kangri well-placed under my phiran. Beside me is the usual and everyday figure, Haji smoking on hukkah. He has been here for over a year now. He doesn’t go home. He feels safe in the shelter of an influential Kashmiri. But here too he is not very relaxed. He lives in constant fear. Zamman kaka informs that Haji generally spends sleepless nights getting up at least five times through the night to check if the doors are properly locked. Last year Haji lost one of his sons in a military operation. He was a militant. The other son is in the security forces. And Haji is at the vertex of this triangle. Militants suspect him of helping security forces, while the police and the army have their eye on him for he is the father of a slain militant. You greet him and he greets you back with a smile. But behind that smile his troubled past that’s still haunting him is hardly concealed.

Quyum saab has left and so we hire a taxi and drive to Srinagar. It’s 31st and so a reason to party which basically means drinking. The diea of coming to town was basically to meet Javed Jalib, an old acquaintance and quite a colourful (can say literally too: with white complexion and red hair he wears a bright red jacket with blue pants and white shoes) person to be with. After walking a bit through Poloview and parks around we decide to move to probably the sole bar in town (I can’t remember the name so forgive me for that). Openly drinking is still a taboo in the Valley. But there are a couple of wine shops in town and considerable crowd can be seen at the counters. Liquor is to Kashmir, what sex is to India. Everybody does it but in their bedrooms.

The security is heavy at the bar. But then security is heavy anywhere you go in Kashmir. For that matter, the forces are only happy to see Kashmiris drinking. There are remote chances of a drunkard turning a militant. The guard at the gate asks us, “Koi asala to nahi hai aapke paas?” We say, “Asala to nahi par Masla hai chahiye.” We share a laugh and move on. It’s a small rickety bar, but full of youngsters sipping on beer. We spend the next two hours talking and its time rush home now.

Midway we stop at Harwan and are greeted by huge tents and decorations at the police station. We are informed that it’s all part of the preperation for the New Year bash. The folk musicians could be there anytime and so the munshi insists that we must stay back and enjoy the musical evening, the first of its kind in Kashmir. First of its kind because the stressed out men in the police and the forces are never treated to such niceties in Kashmir. They are just expected to do their duty in harsh conditions and wait for holidays as relief. Faisal says, “I want maximum work from my men and for that to happen they also need such relief.” But we have to rush home as it’s getting dark. We wish the men a happy new year and move on.

At home the bonfire is ready. Leaping flames fighting the biting cold, around sit red faces in crimson light roasting Kasher Kokar, glasses of Old Monk rising in a toast (forgive me for this sentence). Couldn’t have imagined a better New Year. But probably the best was yet to come. At around 9:30pm we suddenly decided to visit Harwan. Cramped in a Scorpio some 10-12 of us reach Harwan where we see the party is in full flow. The village folk band has been playing for an hour now and the policemen are dancing in full masti to the tune of ‘Rind posh mal…’ We too join the fun and in a while almost everybody is dancing. The singers are tired but are being forced to keep singing as who knows when this fun would visit again. And finally an eventful day ends with, as usual, a heavy meal.

[ This is for those who know Amit Sengupta: Many Kashmiris I met also knew Amitda. And the perception is that he is a medico. You know ‘Doctor saab’]

The raid in Dara

December 30, 2005 The alarm in my phone rang exactly at 7am. I heard it clear but kept sleeping. Couldn’t muster enough courage to get up and put it off. As an outsider in Kashmir winters you can be woefully short on this courage. We somehow got up at quarter to 9 (in the morning itself). We had to leave by 9. Taking a bath was out of question, not that we wanted to anyways.

The alarm in my phone rang exactly at 7am. I heard it clear but kept sleeping. Couldn’t muster enough courage to get up and put it off. As an outsider in Kashmir winters you can be woefully short on this courage. We somehow got up at quarter to 9 (in the morning itself). We had to leave by 9. Taking a bath was out of question, not that we wanted to anyways.

We somehow got out of the house by 9.30, sat in Quyum Saab’s Maruti Omni and drove off. (BTW we also stayed at his place.) A cigarette lit up meant the whole car was full of smoke within minutes. I was choking; I don’t smoke, if you want to know. All efforts to roll down the window failed. It had frozen, at least, that’s what they told me. With three layers of sweater, a jacket, feet well packed (with three layers of socks I would like to call it that way), and an airtight car, we were still shivering. By the time we reached Harwan Police Station, wherefrom we had to accompany a police squad on a raid in Dara, a small village 15 km from Harwan, we were badly in need of a heater and a couple of hot cuppas. Rushing to the DSP’s room we did exactly that. Faisal, the DSP on probation, was busy making plans and arranging for the New Year bash for his men.

In about another half hour we were ready to move. While Faisal and his team drove in their BP (that’s what they call a bullet proof Gypsy there), we sat in an Indica, confiscated by the police a few days ago. But it wouldn’t move. The fuel had frozen and after about half hour of pumping (that’s how they put the problem and the solution across) in the middle of the road we moved towards Dara.

Traversing the meandering road uphill, flanked by breathtaking landscape on either side I completely forgot I was going on a raid and not on honeymoon (Don’t get ideas, just because I was with a man!). I was clicking pictures like a madman of every stupid thing around. All along the way we kept a safe distance from the BP. It’s not a very good idea to be chasing a running coffin.

As we reached the village all eyes were on us i.e. the police and we two. Villagers knew the next few minutes could be full of action. Everyone on to his window, door, or even the road overlooking the house to be raided. The terrain is such that wherever you stand you are exposed to 10-15 houses.

The policemen take their position, while we maintain a distance (can’t call it safe) at the same time try not to lose sight. The DSP opens the rickety tin-sheet door with a kick, Slam!!!! Suddenly there is commotion and loud noise of tumblers falling, as if someone is trying to escape, women start shouting, the policemen tighten their grip on the trigger and we have our heart in mouth. Oh! It was just a dog that jumped on the stranger in the house. The police spend some time interrogating the family. The man they were looking for hasn’t come since last night, they are informed. He is suspected to carry ration to the militants in the jungle.

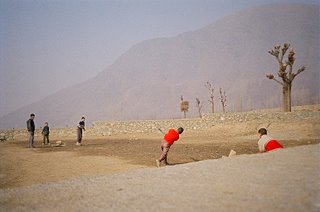

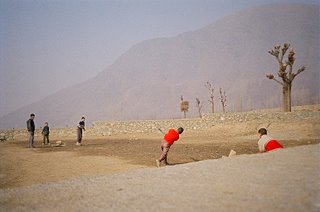

We return back, stopping in the middle to click pictures of children playing cricket. Cricket seemed to be quite a popular game in Kashmir. Everywhere in cramped lanes we could see children playing the game. On our way back from Wusan, some time later, two youngsters ferociously discussing cricket are quite optimistic about India’s tour to Pakistan. “Harbhajan is in top form. I tell you, he is going to rip through the Pakistani batting line up.” We don’t quite agree but move on.

We return back, stopping in the middle to click pictures of children playing cricket. Cricket seemed to be quite a popular game in Kashmir. Everywhere in cramped lanes we could see children playing the game. On our way back from Wusan, some time later, two youngsters ferociously discussing cricket are quite optimistic about India’s tour to Pakistan. “Harbhajan is in top form. I tell you, he is going to rip through the Pakistani batting line up.” We don’t quite agree but move on.

Apologies for verbosity, I was just a little excited

Descending in the Valley and after

Let me start with a disclaimer, for it is necessary. My knowledge about Kashmir, the paradise, the hotbed of militancy and many more things, is all derived from what I saw and experienced in my 10-day stay in the Valley as also like most of us from reading on Kashmir in the media. I have tried my best not make generalised statements but if any subjectivity has crept in it is entirely by mistake and not by design. It will be a series of articles narrating every day of my stay and interaction with people in Kashmir. I hope to update everyday but may miss out because of the busy schedule of my work. So apologies in advance. Here we go:

December 29, 2005

Rushing to the airport more than an hour in advance to book a window seat was of no consequence. As the flight took off the fog reduced the visibility to not more than 200 metres (I don’t quite know how much, but things were just not visible). However, as it descended in the Valley, there was some solace for someone who was visiting it for the first time. The reduced height gave a breathtaking view of the snow-clad Himalyan peaks fighting for space with cotton white clouds. I literally felt I had attained salvation and was descending in paradise. And the moment I touched the ground I knew I was there. The breath of fresh air seemed to open every orifice of my respiratory system. It was like sniffing on mint. It can give you a high, incomparable to any other you have had.

We were lucky to have someone receive us, or else for a newcomer it can be a very costly affair. Taxis here can fleece every penny out of you for a 10 km travel. As we drive through downtown Srinagar, an array of beautifully constructed houses, typical to a hilly area, are puncuated by remnants of a decade and a half of Kashmir’s troubled history. Houses with telltale signs of either being set on fire by militants or blown apart by the security forces during an operation. The owner has to fend for himself. No accountablity here, on either side. For militants it's price you pay for freedom, for the security forces it's collateral damage. The serenity of the placid Dal lake adorned by the beautiful houseboats and shikaras, the symbols of the paradise, can be very deceptive. The paradise is no more what it was in '50s and '60s. Probably, it is no more a paradise. For there is constant fear. Fear of the militants, fear of the security forces. They are present everywhere. So are the militants, anyone could be one. The road bordering the Dal lake later leads to Gupkar Road where the high and mighty in Kashmir live: Farooq Abdullah and others. These are high security zones with heavy military presence. If you want to know, high security zone in Kashmir means where the next attack is going to be. It's almost like the 'yahaan-peshab-karna-mana-hai' phenomenon, which generally ends up being an indicator of the place to pee.

Kashmir is more disturbed than what we know through the papers, and so isn’t it dreadful a place as many journalists would want us believe. Kashmiris are genuinely nice and innocent people who will greet you with amazing hospitality. Every time we struck a conversation with a stranger regarding our work or even to ask a direction and it was revealed that we were outsiders, we were invited for dinner and even stay.

Though the focus of the militants in the past five years or so has shifted from civilians to the security forces, Kashmiris still can’t relax. If in the tussle between the security forces and the militants anyone has suffered the most and still suffers it's the innocent people. Guarding Kashmir against militants is also not easy. You are always on your toes, even when not on duty, because you are always on target. The hydra of militancy has spread its tantacles far and wide, and heavy military presence can never uproot it. I do not know what can, because even the highly talked about peace process has had no effect on militancy.

At the Harwan Police Station, some 10 kilometres from Srinagar, squats a 20 something lean and thin boy clad in a phiran, with his hands firmly inside to protect from the biting cold. As you look at his innocent face you feel pity for him. A pity that he does not deserve. In the past two weeks he has slain 12 men at the behest of militants. Not with a gun but by slitting their throat. He is a local labourer and has been used by the militants. He has no trace of remourse on his face for what he has done. No one knows what will be his fate, except the military guys who will pick him up from the police station in a day or two.

We are planning for our dinner and so need to pick some good meat before it is evening. Kashmir means a lot of meat. Nothing will be available once it is dark. So we rush home planning to buy the meat midway. Some 15 kilometres out of Srinagar we notice a shop in the local market and are about to get down when we here shouting and commotion on the road. What we see is, locals say, an everyday affair in Kashmir. Two youngsters holding the barrel of a CRPF personnel's gun and shouting, "Shoot me. Why don't you shoot me? Shoot me know." It was a small altercation where the CRPF man had addressed them, "Saale..." and a fight ensued which could have serious repercussions hadn't a senior officer intervened and reprimanded his deputy for not behaving properly. It was a heartening sight. For a decade ago, the boys would have been shot. Kashmir has changed in the past few years but too late and too little. The locals do not have any faith in the State. Years of excesses — torture, rape and murder — by the security forces has completely eroded the credibility of the government. There is a latent anger against the system in the locals. "Mera Bharat Mahan" is something that can be seen adorning only police and security forces vehicles. No one connects to it here.

The government too is more concerned with security and local governance is way behind in the agenda. There is no local policing either. Right from the top officers in the military to a havaldar in the police is only chasing militants. A murder here, or a theft there does not even register itself to the police unless it is related to militancy. If it does, no one bothers to follow it up or solve the case. Kashmir has been reduced to a cat-mouse fight between militants and the security forces. And the casualty is the masses.

Now a days there is constant power shortage all through Kashmir. And the plan for energy conservation the government has come out with is to ban heaters and water boilers. In -6 degrees, when your jaws can freeze to inactivity, the people have to bear the brunt of the State's insanity. People’s houses are being raided and heater’s seized. That’s quite a way of garnering popular support!